Atonement

This documentary delves into the profound knowledge systems of indigenous communities across Africa, showcasing their sustainable practices and cultural heritage.

Part one: Vodun days

It is impossible to put into words exactly how much pain the African continent went through during slavery. The indelible trauma that was written into a significant portion of the population, the daily raids that arrested the upwards paths of different civilisations, the vast project to devalue the materiality of human beings, it is hard to even imagine the violence that shaped the reality of a significant part of Africa.

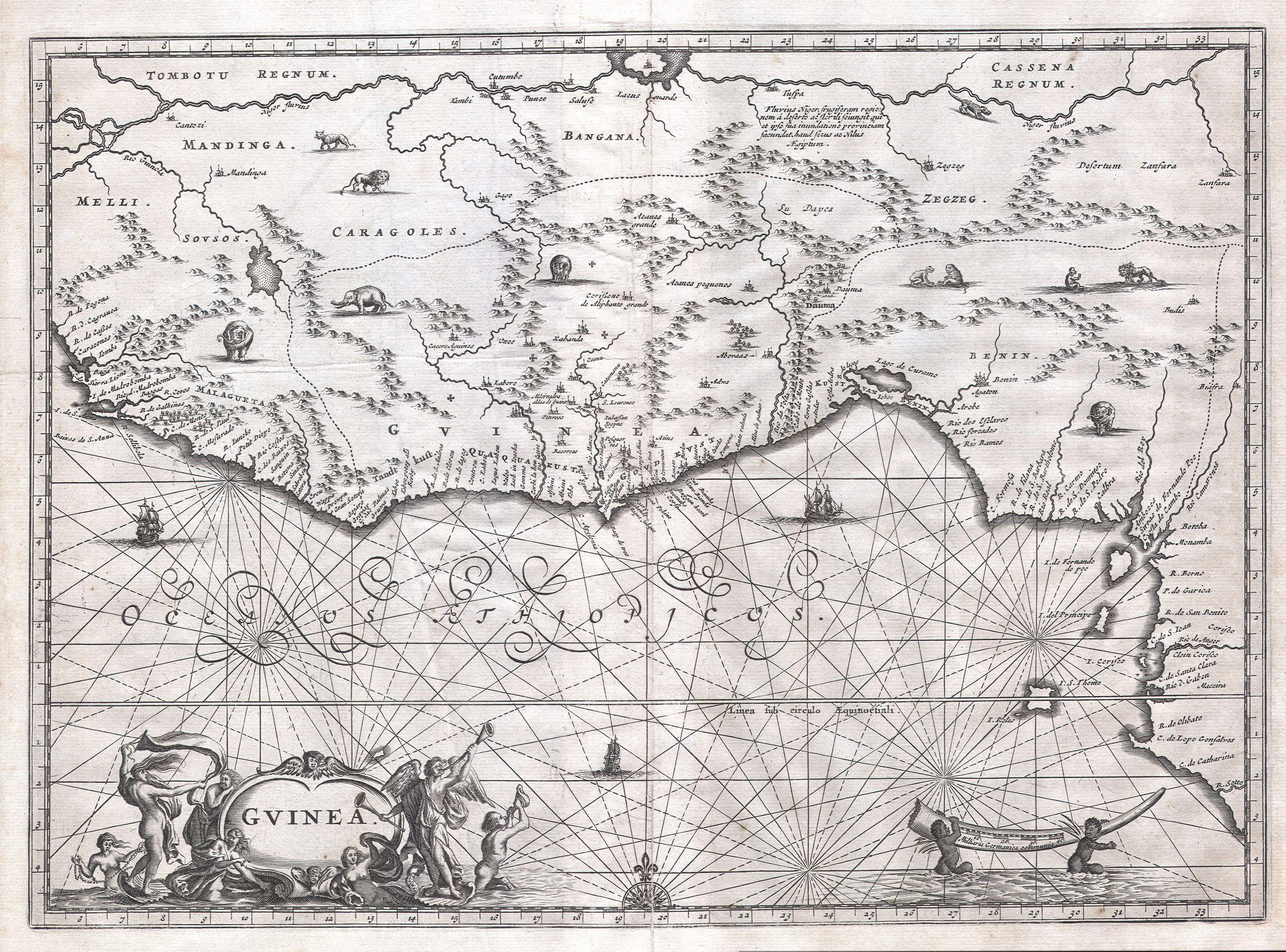

There is a general belief that the transatlantic slave trade shipped at least twelve million Africans to the Americas, notably to the USA, Brazil, Barbados and so on. If we settle on the argument of twelve million slaves for argument’s sake, there is a significant group that we do not account for, namely those who died during slave raids, during the march back to holding forts like Gorée, Cacheu, Elmina, Badagri, Bimbia, Sao Tomé, etc., and those who died either because they attacked their guards or sexual predators in the holding cells and those who committed suicide rather than live in captivity. You can see how that created unspeakable trauma on both sides of the Atlantic.

Concurrently with the Transatlantic slave trade, there was also a centuries-old slave trade on the Indian Ocean Swahili coast. Starting from the seventh century, as islam spread southwards, millions of slaves were taken northwards into the Ottoman Empire, Persia, India, etc. The Indian Ocean slave traders was dominated by people like Mwinyi Mkuu, Sultan Seid Sayid and the infamous Sultan Hamad bin Muhammad bin Juma bin Rajab el Murjebi, a.k.a. Tippu Tip. The Transatlantic, Trans-Sahara and Indian Ocean slave trades emptied Africa of at least half its population by the time slavery ended.

Slavery’s impact on Africans and their environment is incalculable. The pain and trauma can never be repaid. However, there is growing consensus that some form of atonement needs to happen, both in the communities where people were taken from as well as in the places where they were taken to, held against their will and exploited for centuries.

It is possible to calculate just how much slaves contributed to the places they were taken to. While the main drivers of the slave trade made vast amounts of wealth, the descendants of slaves and the communities that they came from are still scarred by the trauma of this scourge. However, beneficiaries of slavery often retort: “who do we pay reparations to and how much?” This is a disingenuous question of course. We know where slaves were taken from. It is also possible to trace the main beneficiaries of the slave trade.

Proceeds from the slave trade funded a large part of the modern global economy. After slavery was abolished, those who had made incalculable wealth from it took their profits, and reparations in some cases (France, England), and reinvested it in emerging areas like railroads, plantations in Africa and the Global South, etc., and that money has been recycled dozens of times ever since. Registers of slave owners (which can be accessed through the National Archives UK, National Archives USA, etc) are important places to trace the direct link from slavery and colonialism to some of the biggest companies in the world today. To quantify in real terms, we are talking about trillions of dollars.

After the end of slavery in the USA, African Americans were promised 40 acres and a mule, but this never materialised of course. What happened instead, from the USA to Europe, is that governments spent a large portion of their budgets paying reparations to former slaveholders.

African countries whose populations, culture and governance systems were decimated by slavers and their funders in Europe and America are joining forces with descendants of slaves to demand reparations. The African Union’s theme of the year is Justice for Africans and People of African Descent Through Reparations.

Former Ghanaian President Nana Dankwa Akuffo-Addo held an international conference on the topic in 2023. Speaking at the opening of the conference, he said: “"No amount of money can restore the damage caused by the transatlantic slave trade. But surely, this is a matter that the world must confront and can no longer ignore".

.jpg)

An African example of Atonement

Atonement does not always necessarily mean paying cash money. The Republic of Benin has been doing a different form of atonement for over two decades.

Although credit has always gone to Nicephoere Soglo for launching Vodun Days tradition, the idea was first discussed at a UNESCO event in Haiti. The idea behind Vodun Days was to serve as an immaterial umbilical cord that symbolically reconnected diasporic Africans to their roots. These Africans could not just go back to a land that had not been cleansed of its sins.

On the 500 year celebration of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in America, former Benin President Nicéphore Soglo met with some important partners, including UNESCO and France, and decided to host a remembrance event in Ouidah entitled Ouidah 92 - Retrouvailles Amériques- Afrique. The purpose of the celebration was to:

- Break the silence surrounding the tragedy of the slave trade and slavery by contributing to a better understanding of its root causes, the issues at stake and its modus operandi through multidisciplinary scientific multidisciplinary research.

- Shed objective light on the impact of the slave trade and slavery on modern global transformations and the cultural interactions between peoples between peoples that this tragedy may have generated.

- Contribute to the culture of peace and peaceful coexistence between peoples, by encouraging reflection on cultural pluralism, the construction of new the construction of new identities and citizenship, and intercultural intercultural dialogue.

For the occasion, UNESCO Deputy Director Noureini Titjani-Serpos conceived a three-kilometre open-air installation that started at the Ouidah city centre and went all the way down to the sea shore where a door of no return was erected. The route itself was baptised the Slave Route (la Route de l’Esclave). It features six stops:

- The auction square where Francisco Felix da Souza once oversaw the auctions;

- The tree of forgetting;

- Zomai house;

- Zoungbondji Memorial;

- The tree of return for the spirits of departed slaves; and

- The Ouidah beach where slaves were loaded onto slave ships.

Significance

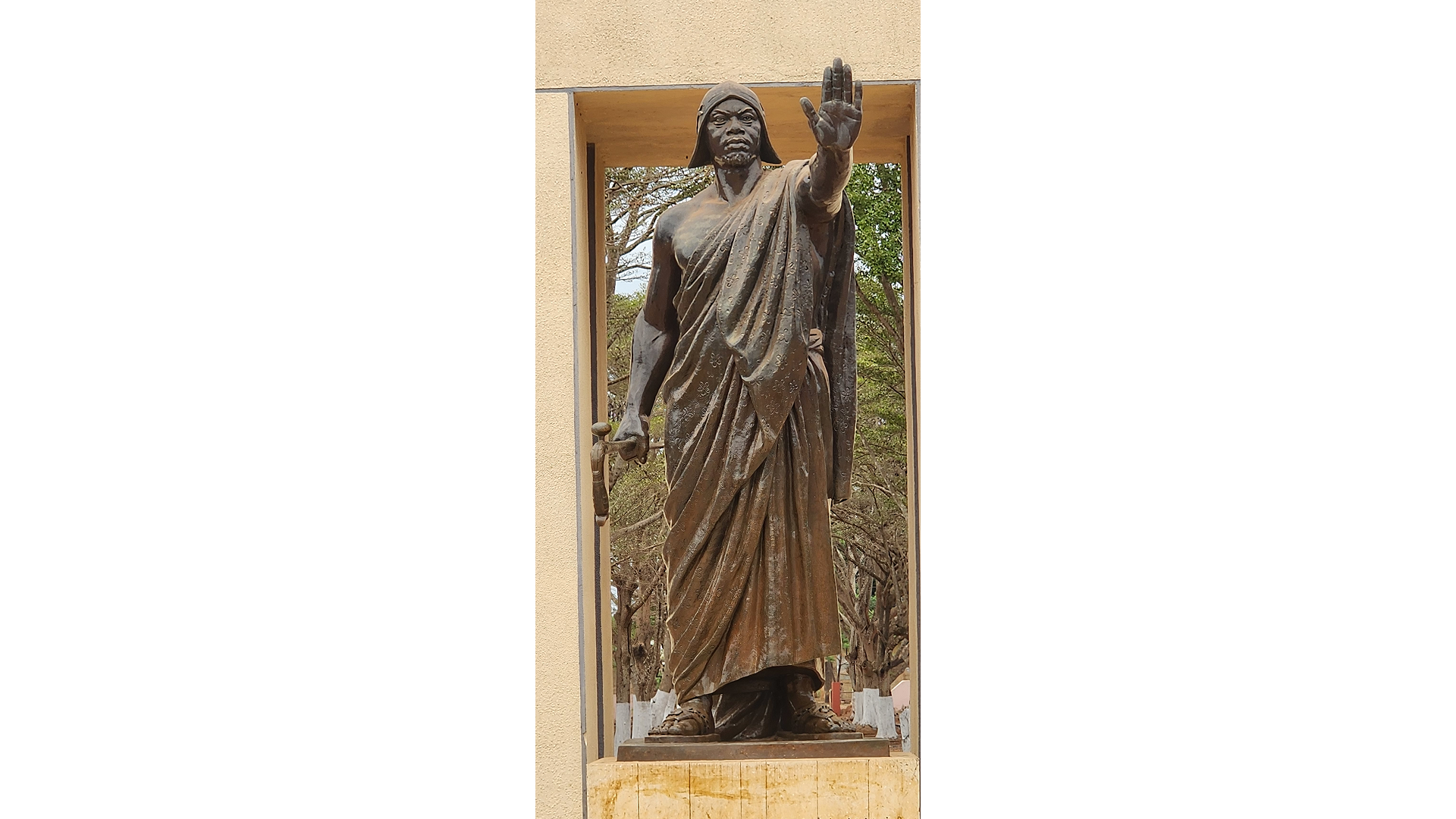

Dahomey (today Benin Republic) and neighbouring Oyo (Nigeria today) were key players in the slave trade, buying and selling millions of Africans. Hundreds of thousands were likely killed during raids, while evading capture or in holding cells. The Fon kings of Dahomey were prolific sellers of slaves. Starting from the reign of King Houegbadja, their forces captured hundreds of thousands, if not millions of Africans who were then sold to the many European slave ships that landed frequently on their coast.

The sleepy town of Ouidah belies the outsized role that it played in the slave trade. Many descendants of slaves in Brazil and all across the Americas were taken from Africa through Ouidah. Dahomey’s participation in the slave trade ended only in 1984 when Béhanzin’s forces were defeated by the French army.

Vodun days are the opportunity for all the Vodun deities to come together and pray for the souls of the millions who perished on African soil or in the Americas. A Vodun priest explained during the first Vodun Days that the event was not really about asking for forgiveness. Rather it was a gathering to pray and release all those who were taken into captivity, all those who died and the descendants of enslaved people from their suffering so that they should suffer no more.

II: What is Vodun?

Origin of the Vodun Philosophy

Vodun is part belief system, part life philosophy and – more recently - part religion. Vodun followers believe that the living and the dead inhabit the same space all the time. In fact, we are already dead when we are born and so there is no reason to fear the world beyond. Nature around us is alive and there is life force in everything.

In the Fon language spoken in modern-day Benin Republic and other neighbouring countries, Vodun refers to the Creator or almighty spirit, that which cannot be described or even named. This omniscient, omnipotent spirit is sometimes referred to as Mawu Sagbo Lisa. It is also called by the Yoruba terms Olorun, Olódùmarè or Eledumare. The Haitian Creole words Gran Met (Grand maître) and Bondye (Bon Dieu) refer to the same entity.

It is important to note that the Fon always use the word Vodun with a voiced velar nasal n (ŋ) when referring to their divinities and spiritual systems. In neighbouring Togo, the Aja typically say Vodou (the n is dropped and so what you hear is vodu) while the Gan and Ewe of Ghana have embraced the Hollywoodised word Voodoo, for better or worse, although it must be said that many followers will always refer only to the specific divinities that they worship and never to an all-encompassing voodoo. In any case, it is quite complicated to understand the entire pantheon of divinities, something that the average person is too busy with the challenges of daily life to bother themselves with. That job is for the priests and diviners. In Haiti, they use Vodou.

Vodun was born in West Africa where many years of upheaval and migrations spread Yoruba spiritual beliefs to the Fon, Aja and Ewe who are predominantly spread around Eastern Nigeria, the Republic of Benin and Togo. In Benin, the belief system itself borrowed heavily from the Yoruba pantheon.

According to these and other communities in West Africa, the world is full of energies (voduns or as Haitians call them Lwas). There are Lwas in everything around us: in the trees, the animals, stones, mountains, rivers, birds…everything. These Lwas may be benevolent, malevolent, mischievous, etc. They are organised in a hierarchy, based on their strength and closeness to the supreme force. Human beings also have affinities with different Lwas based on the day they were born! In Vodun, each day of the week is connected to one of the four elements (earth, air, fire and water) and therefore to different Lwas. Different parts of the body also have different strengths and capacity to repel or absorb evil.

We are all spirits and the day we are born, we are already imbued with energies and so we can attract energies based on the sacrifices that we offer to Lwas through the deities that embody their existence. The deities are organised in a hierarchy, similar to the Yoruba pantheon, from Mawu Sagbo Lisa at the very top, followed by its immediate messengers and then lesser deities, of which there are literally thousands.

The most important messengers of Mawu Sagbo Lisa include:

- Ogun, the deity of iron and war.

- Mami Wata the deity of water and fecundity.

- Xevioso: the deity of thunder.

- Dan: the python deity of wealth, death, travel and skills.

- Shango: the deity of masculinity, dance, virility, and violence.

- Legba: the gatekeeper or key-master.

Legba is the deity that facilitates communication between human beings and other deities. It is often represented in the form of a cross during a séance. To speak to other deities, one has to ask Legba to open the channels of communication to them or maybe even to take the message to them directly.

The next level of divinities include:

- The Zangbeto: the guardians of the night, based mainly in Agbodrafo, Togoville and Grand Popo

- Dangbe: python deity of the Xweda.

- Guelede: deity of the origin of the world as well as the future.

- Egun: deity of death and revenants.

- Koku: warrior deity of violence

As you can see, depending on where you are, the level of the deity could be higher or lower. Koku and Shango are very similar in their behaviour. The same goes for Dan and Dangbe.

In the minds of the Vodun faithful, there is no contradiction here because Vodun should not necessarily be viewed as a codified system with laws that are set in stone. Rather, different communities adapt it to their needs and lifestyles, and what happens in Togoville (Togo) may not necessarily exist in Port-au-Prince (Haiti).

Vodun priests spend about seven years in a monastery to learn how to communicate with Lwas and interpret their messages. They learn how to decipher messages transmitted by people during spirit possession. They also learn how to do Fa readings. Fa reading, which is the same in Yoruba belief system, is alleged to have originated in Kemet (ancient Egypt). It is associated with Orunmila, the deity of wisdom and prophecy. It was brought to Ile Ife before spreading to other parts of West Africa. Ifa divination is based on 256 organising principles that control every aspect of our lives, including birth, life, death and rebirth, organised in 16 chapters or Odù. Each chapter is dedicated to solving a different problem: long life, health, etc. Fa priests or Babaláwos use chains called Ọ̀pẹ̀lẹ̀ to mathematically identify which chapter to use to solve a particular problem that has been brought to them. They may also throw kola nuts (Ikin) or other objects on a wooden divination tray (Ọpọ́n Ifá) to identify the solution to a problem.

People invoke the help or protection of deities for different reasons. Before undertaking major projects, people offer sacrifices and try to consult Fa readers to see whether their undertaking is going to go well or not. If there is the possibility that something could derail their project, they offer sacrifices and invoke deities to make their pathway clear. If their prayers are granted, they go back and give the deity an offering.

During invocation sessions, priests use different methods like music, prayers and dancing until the Lwa possesses one or more of the assembly to transmit messages through them. To summon a Lwa, one offers the deity some of things that it likes. Some deities prefer palm oil, others prefer alcohol, some accept only sweet things, others blood, and so on. You may not offer palm oil to a deity that has a sweet tooth for example. That is a mistake that could completely kill the potency of its shrine, a mistake that possibly cannot be unmade or maybe it could take years to fix.

The principles of Vodun

Vodun has many different principles. You should not necessarily view them as existing in a hierarchy, but rather as the different laws on which the entire structure stands.

The number one law of Vodun is do no harm. This May come as a surprise to you, considering everything that you may have heard about Vodun in movies and conspiracy theories. Vodun priests often say that we can invoke energies to do anything we want, good or bad. However, if you invoke an energy to harm someone whose hands are clean, the evil you unleash shall come back to hurt you. Think of it as Karma. You send out bad Karma, you receive bad Karma. You send out good Karma, you receive good Karma.

Secondly, there is an explanation for everything that happens to us, good or bad. We have all kinds of questions that go through our minds at different times. Vodun is the light that gives clarity to people’s lives. When we want to know our purpose on earth, how a major project is going to go, how to change fortunes after a series of mishaps, and so on, we seek clarity or protection from a deity.

There is energy in everything and so we need to maintain a careful balance between taking from nature and giving it time to heal and regenerate.

The different plants and animals around us have different potencies and energies. They can help us heal diseases or change our fortunes. Babalawos and Vodun priests spend many years learning the names and uses of different plants.

Forests are particularly important and Vodun believers say that it is important to preserve forests as well as water sources so that they can keep helping us.

Increasing attention on Atonement

Benin is acknowledging the role that some of its parts played in the slave trade. It is, very actively, also acknowledging the importance of recognising and praying for not only those who were taken away to the Americas, but also those who were violently attacked in their homes, on their farms and on other places just doing normal everyday things that we do without a second thought. It is acknowledging the millions who died between Africa’s hinterland and the Slave Coast. That is very important.

Other African countries need to do more. A small investment in properly maintaining the forts and holding cells where slaves were held before they were transported to the Americas is a good start. Many African Americans, afro-Caribbeans, afro-Brazilians and other diasporic Africans come to the Slave Coast every year to get a better understanding of how their ancestors were captured and taken from their lands, and I am sure that when they see the neglect and advanced state of disrepair in which some sites are in, that feels like a hammer blow. A number of really important sites in Badagry (Nigeria), Togoville (Togo) and Bimbia (Cameroon), as well as others in Guinea Bissau, Sao Tome and Angola have been abandoned to the elements and that needs to change.

Elsewhere there are revisionists like Nigel Biggar and others who engage in culture wars and denialism, rewriting history to explain away that slavery and colonialism was not all that bad and that they did not do much for the Global North’s growth.

Fortunately, the databases of slave owners still exist. The databases of slave ships and their owners still exist. The databases of those who received reparations in countries like England and France still exist.

Fortunately too, researchers like Thomas Piketty and David Olusoga are doing sterling work to show how the proceeds of slavery built some of the major corporations that run our businesses and affairs today.

It is still fairly common really, to hear comments like: “well, why don’t you also ask Arabs to pay reparations?”, “Why should we apologise when we were never there?”, “Who should we pay reparations to?”

Those who make such arguments however never admit that they were happy to receive generous inheritance built by slavery.

The Church of England, Harvard University and others have made bold steps towards acknowledging the part that they played in slavery or the wealth they got from it and they have already adopted policies or programmes to help descendants of slavery get some kind of reparative and restorative justice.

Going forward, we need to broaden these discussions in order to better understand how proper and significant reparations should look like.

.jpg)

.jpg)