The Moaaga philosophy and the challenges of the 21st century

The Moose or ‘Mossi’, who settled in what is now the central north and central north regions of Burkina Faso, created one of the most important socio-political formations in the Niger Belt as early as the 14th century.

Factors such as their system of inheritance, their socio-political and administrative organisation and their religion based on the worship of the land and ancestors, among others, have positioned them among the most important entities. Indeed, for centuries, the Moose lived almost on their own, even during the ferocious expeditions of the great Almamis, who were both converters of infidels and conquerors of immense lands, and during the incursions of the European colonising powers. Some observers even speak of a ‘golden age’, to characterise this period during which they considered themselves ‘independent’ and free to organise themselves.

Nevertheless, since European colonial expansion in Africa at the end of the 19th century, the Moose have been caught up in the spiral of French domination, without ever again having the opportunity to live according to their former conception, their own vision of the world. This new situation, with its impact in terms of transforming their philosophy of life, has broken their momentum and hindered their progress in the process of building a universal civilisation, excluding them in a way. Today, globalisation, a system that is changing the entire planet, has engulfed them further in the logic of the capitalist economy, with its corollaries of total monetarisation of their exchange systems and the monopolisation of all their social relationships by profit. This globalisation, which above all continues to transform their spiritual, technical and material concerns, does not only benefit them. It denies them the possibility of being themselves and of existing as contributors to the heritage of humanity.

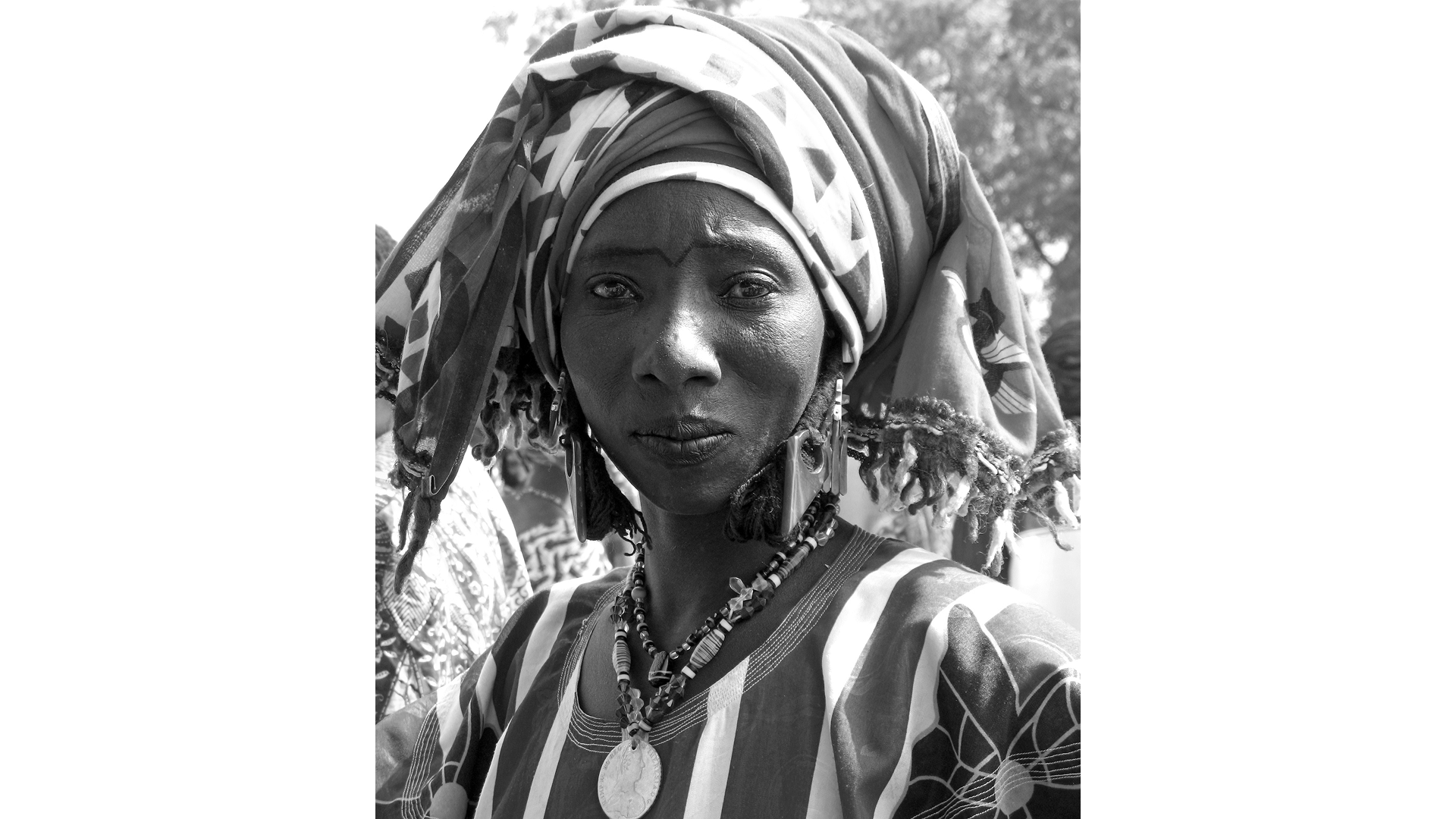

.jpg)

However, their life philosophy offers many solutions that could provide alternatives to the excesses and excesses of the hegemonic capitalism imposed by globalisation, which current generations can draw on to change their way of being and living in a more ‘humanised’ world. This study is concerned precisely with those aspects of the Moose philosophy of life that are useful and topical, and that could be reactivated and taken into account to ensure better connections between people in today's world. The aim here is therefore to analyse traditional Moaaga philosophy in the light of the major challenges of the 21st century. Specifically, the aim is to:

- show the basic principles of traditional Moaaga philosophy;

- present the main environmental, social and spiritual challenges of the 21st century;

- analyse the adaptations of Moaaga philosophy and develop an essay on how this philosophy can offer responses to contemporary challenges, while retaining its fundamental values.

Before discussing traditional Moaaga philosophy, it is important first to show how this people was constituted and how it has evolved.

Historical background: who are the Moose?

The Moose or ‘Mossi’ are a people who live in a territory formerly known as ‘Moogo’, a term that can mean the universe, the world, but which we use here to refer to the area inhabited by this people in Burkina Faso. According to Michel Izard, this territory was made up of nineteen kingdoms grouped into three clusters around Tenkodogo in the south (Lalgaye, Wargaye and Tenkodogo), Wogdogo or Ouagadougou in the centre (Kayao, Konkistenga, Yako, Tema, Mané, Boussouma, Boulsa, Koupela and Wogdogo) and Yatenga to the north (Bousou, Darigma, Niessega, Rissiam, Zitenga, Ratenga and Yatenga), between 10° and 14° north latitude, and 0° and 3° west longitude. It currently corresponds to the location of the thirteen (13) provinces, covering an area of 70,448 km², or 32% of the national territory (L. Simporé, 2005, p.46).

When one of them was asked if he was a Moaaga (sing.= Moose), he did not hesitate to specify that he belonged to a Moaaga sub-group, to say that depending on the region, the composition of the people was different. Thus, in the Tenkodogo region in the south, the first Moose were Mamprusi-dagomba who cohabited with Zoase, Yarse, Bisano and Nobdamba to form the primary Moaaga ethnic group in the 14th century. In the centre around Ouagadougou, elements from this primary group mixed with other groups such as the Yonyoose, Ninsi, Gurunsi, Sana and Kurumba. Finally, in the north and centre-north, the social fabric differed with the integration of the Ninsi, Kurumba, Songhay, Peul and Gulmanceba with the descendants of the Moose-dagomba. Then, between the 15th and 19th centuries, Yarse (Dioula), Haousa, Djerma and Peul also settled in Moogo.

The term ‘Moose’ or ‘Mossi’ and ‘moaaga’ in the singular is of Mampurga origin. It was originally used to refer to the inhabitants of an area neighbouring the Mampurga country: Moogo. Based on the diversity of the groups that make it up, Michel Izard and Joseph Ki-Zerbo (1986, Pp421-422) state that: ‘...the term moaaga/mossi means mixed, mixed race’. In short, the singular ‘Moose’ and ‘Moaaga’ means mixed race, composite group.

.jpg)

Overview of traditional Moaaga society

Traditional Moaaga society was hierarchical. It was made up of families comprising patrilineal lineages organised into strata. At the top of the hierarchy were the nobles, who were the descendants of the founders of states (nakombse). Then there were the freemen (talse) and the slaves (yembse). Socio-political organisation was based on these strata and on a conqueror/slave model, with the former holding political power (naam) and the latter religious power.

The term ‘naam’ is equivalent to ‘political power’, a power held by the Nakombse and deserving men. Naam was materially symbolised by royal fetishes (naam-tiibo) which conferred on the holder the ability to act on people and things using a wide range of means, from persuasion to coercion (Balandier G., 1966, Pp 42-43). The naam was the most effective instrument that enabled the Moose to defend their society against its own weaknesses, to keep it in good condition, to ensure respect for the rules on which it was founded and to give the society the means to assert its personality and identity. By virtue of its dual historical and sacred origins, the naam elevated the prince among the divinities, and the personality of the Moog-naaba, a kind of supreme chief, symbolised, beyond the Moaaga people, the sovereign of the entire universe.

Among the nobility, there were several strata, ranging from the supreme nobility (rim-damba and rim-bi), to provincial chiefs (kombemba), village chiefs, neighbourhood chiefs and family chiefs.

The title of nobility was also awarded to individuals from other categories of society without distinction, for their merit and to involve them in the administration of the country. This was the case for the dignitaries of the sovereigns' courts, some of whom were former slaves and foreigners.

Alongside these holders of the ‘naam’, there were those to whom the management of religious power fell: the teng'nbiisi or ‘people of the land’. They generally came from the communities that the nakombse found when they arrived. The teng'nbiisi were considered to be priests with supernatural powers to control cosmic and natural forces (clouds, winds, rain, etc.). Teng'nbiisi communities were headed by teng-soabendamba (sing. = teng-soaba) or land chiefs. The teng-soaba of a village was the overseer responsible for managing the land, the priest of the ancestor cult and the principal sacrificer to the ancestors. As the most senior member of his lineage, the teng-soaba was feared and respected.

For the nakombse, the teng'nbiisi were the true owners of the land and of the secrets associated with its productive management. As they were only occupants, the Nakombse relied on their science to solve many problems, including that of state power. The teng'nbiisi helped to predict the chances of the new nakombga chief, the happy or unhappy events to come throughout his reign, and the length of his reign. They were also able to predict whether the choice of a candidate would usher in a period of happiness or misfortune (famine, epidemics and drought) for the kingdom. Wherever there was a naaba (nakombga chief), there was always a teng-soaba who assisted him in religious and cadastral affairs.

The talse or free men served the nobles and worked for them. They were the subjects of the nakombse and enjoyed their right to security, protection, respect and dignity. They formed the popular mass, the plebs. As such, they could neither be enslaved nor sold. Moreover, every sovereign found esteem and consideration in having many talse in his kingdom, a sign of common well-being and the blessing of the ancestors.

As for the yembse or slaves, they came from the spoils of war, raids and other takings from weaker neighbouring communities. However, slaves were quickly integrated and assimilated into an adopted family, and could earn their freedom and citizenship through hard work and merit. They could also own property (land, women, children, cattle).

Moaaga society also had its engineers, its scholars and its mediators: the blacksmiths. In the Moaaga cosmogony, the blacksmith is considered to be the first human being whom God sent to earth with fire and iron to illuminate the world and put people to work so that they could produce enough to feed themselves. Presented as the mediator between heaven and earth, it was he who intervened when lightning struck to appease the anger of the gods and ancestors. In the event of a dispute between these two entities, it was up to the blacksmith to intercede to prevent the burning earth from falling back into its original chaos.

The blacksmith was also a mediator between men and between them and the ancestors. He initiated funeral rites and produced the tools used to cut wood, administer death, slit the throat of sacrificial animals and heal wounds. In short, the forgéron was the indispensable individual for everyone. How did Moaaga society function?

Structure and functioning of society

The Moaaga people can be defined as a comglomerate of social groups dominated by nakombse and autochthonous groups, which have been continuously superimposed by numerous other groups. To better assert their authority over others, the Nakombse placed members of their families in the various occupied territories. They involved the other communities in the management and organisation of power, taking into account their institutions, customs and religion, as well as their concept of self-government. This enabled them to unite around themselves to form a solid social entity in which the links held together as if welded. It was primarily through the naam (power) and the sovereignty it inspired that their philosophy of unity manifested itself. The authority of the naaba, the holder of the naam, was imposed and recognised throughout the territory, and everyone owed him respect and obedience. After the sovereign, each moaaga was granted a place in society to form a pyramid, enlarged at the base by the aggregation of individuals around families, families to form neighbourhoods, villages, provinces, kingdoms, and kingdoms to Moogo, seen as the territory but also and beyond, the universe.

Representation of the universe

For the Moaaga, everything that exists is the work of an omnipotent and omnipresent god: Wende. This god is located in the sky and is represented by the sun, windga or wind-toogo. Wende has created things once and for all and no longer cares about the details of life on earth. Man addresses him through tenga (earth), conceived as a goddess, Wende's wife. The rain that falls from the sky comes from Wende to fertilise the earth and give life. This life, which comes from God, is preserved in a double world that replicates our own. The universe is thus organised into two poles: one visible and the other invisible. The visible world is where people and things are, while the invisible world is the domain of the dead, the spirits of nature and the lives to come. Each world has its day and its night, its earth and its sky, its waters, its hills, its beings, and the passages that allow us to enter the other either by death or by birth. Everything that exists has its double in the other world.

In this scheme of things, the earth (tenga) in which the living are located is not an objective entity that can be adequately defined using economic concepts alone. It is made up of relationships with people, with complex situations whose religious, social and economic implications are intimately interdependent. Tenga is a very powerful goddess, the very symbol of fertility. Her entrails are the place of retreat where supernatural forces and past existences (ancestors) are collected and kept active, and a reserve of vital principle for future lives. It is in her entrails that she maintains the seeds fertilised by the rainwater dispensed by Wendé to produce the trees and crops essential to mankind and other living beings. It is in her entrails that she welcomes and protects the kinkirsi, the genies who live in nature, in the sacred woods of the village. Their presence guarantees the procreation of women and thus the continuity of the groups. For this reason, the Moaaga carefully tended these groves.

A man could not be denied access to land unless he had committed an unforgivable fault. For individuals who lived in accordance with the laws of society, tenga was the fundamental link between them and their ancestors, and ensured the continuity of their lives in an endless cycle of happiness, through renewed births, full lives, natural deaths followed by funerals that prepared their journey to the afterlife and their return to life through new births. In other words, the earth, the kinkirsi, the ancestors and the society of the living were intimately united. Even in certain situations where men had to leave to found new settlements far away, they took with them a bit of land from their place of origin to remain united with the land of their ancestors and the relatives who continued to live there.

The Moose distinguished between teng-nabre (barren land) and tempeelem (white, sacred land).

It was on the tempeelem that social and spiritual life was organised.Here, there was a kind of contract that harmoniously bound man to his environment through a system of reciprocal rights and duties; respect for this contract guaranteed ontological and social harmony. Tempeelem is the domain of the gods, spirits and deceased ancestors. Its reality is evidenced by dreams, by the incidents of everyday life, ‘...by the oft-recognised effectiveness of divination rites and techniques’. It is also ‘the enclosure of the sacred space delimited by a frontier that those who are not entitled to it do not cross without risk...and which...cuts off from the world all that it encloses...’. (Ouédraogo J.B.).

Tempeelem was also seen as a dangerous power that intervened directly in all forms of social control. Any offence committed against tempeelem resulted in severe penalties, ranging from illness and sterility to the death of the guilty individual, his family and accomplice groups. It also provoked social tensions and natural disasters. These dangers, which inspire the most serious fears in individuals, strengthened social cohesion. But it is the role of the land as a source and reflection of the person of the Moaaga that seems to have been decisive.

The Moaaga self-image

Based on his conception of his environment, the Moaaga has defined himself, since creation, as a being with two dimensions, visible and invisible. The visible part of himself is represented by his body, while the invisible part is made up of several elements. For him, the human body made of flesh comes from the earth and returns to the earth after death, through burial, which repositions it like a foetus in a woman's womb where it is kept active, like a reserve of vital principle awaiting the right moment to be (re)born. From then on, burial is not a trivial act, but one that is surrounded by all the appropriate precautions and care. The fleshy body, however, seems to have been of lesser importance than the invisible parts that animate its life: the wuusm, the tuule, the siiga, the kiima and the kinkirga.

The wuusm represents the vital breath, the energy generated by the breath that sustains his life. It leaves the body with man's last sigh, remains active in nature and gives energy to the newborn who utters his first cry, marking his coming into the world. The tuule represents the sudden appearance of man's double in mortal danger. It is so quick that only a few initiates can see it. Every human being and every social group also has a totemic animal with which its members feel a very strong bond and which can influence them throughout their lives. The totemic animal or siiga, considered to be a double, dies at the same time as its human counterpart.

The kiima is the part of the soul that makes the individual moaaga an ancestor. Shortly before death, the kiima leaves the body and lives in the wilderness, joining the ancestors' hut: the kiim-doogo. The purpose of organising a funeral in Moaaga country is to confirm the sentence of the society, which accepts through the rites that the individual has lived honourably, died naturally and deserves to join the kingdom of the ancestors. The kiima of an individual who died abroad and did not receive a funeral is unlikely to live again.

Kinkirga.It is considered to be an element of nature that participates in procreation during mating. The child born is considered to be a kinkirga.The individual retains this status until he has offspring, at which point his status as ancestor (kiima) takes precedence over that of kinkirga.Like the kiima, freed after death, the kinkirga leaves the body and lives temporarily in the sacred woods, under tall trees, in rivers, etc.A woman who wants a child must use her behaviour to attract the attention of one of them in order to be impregnated. The kinkirsi are therefore essential to the survival of the Moose, who respect nature as the source of their life and the origin of their species.

Relationship between the Moaaga and nature

We agree with Louis Vincent Thomas and R. Luneau (1975, p. 155) when they speak of the ‘homo morphic’ behaviour of the Moaaga, for whom nature is the image of man. Being himself a product of nature, he lives in fear of disturbing it and offending a whole world of divinities whose wrath is implacable (Ilboudo p, 1966, p.62). His attitude to nature has evolved over time. The Moaaga conceives of a beginning of the world where the idea of a death full of anguish did not exist. This deathless world was not, however, a place that was blessed and given once and for all. It was the result of an agreement between living beings that allowed those who died to come back to life. ‘God created all beings, and all lived forever’. Nature was well-watered, wooded and bountiful. Similarly, ‘Heaven and earth were close together. This made it possible for every man to cut what he needed from the sky without labour or effort’. But later, the man says he himself was the cause of a brutal and irreversible break in his relationship with nature, following ‘a brutal gesture by an old woman who raised her pestle high and struck the sky’. Wounded and shocked, the sky fled forever into the immensity of the cosmos. And ever since then, people have had to work and produce in order to feed themselves.

Through the myths, we can see that the Moaaga became aware at some point in his evolution that his actions - cutting, gathering, bush fires, farming, livestock rearing, etc. - were causing ecological upheaval and that he needed to be careful. In a bid to regain his bearings, he developed a ‘homo-centric’ attitude, in which he sees himself as a privileged creature occupying the centre of the universe (Moogo), with a mission to dominate other creatures and control everything that exists. He establishes rules that enable him to preserve flora and fauna, select and nurture the species that are most useful to him, and associate some of them with his deepest beliefs in the form of totems.

Moaaga country can therefore be seen as an area that has long been parked up by a system of fairly controlled exploitation of natural resources. Indeed, ‘...favoured by a natural environment that offers him a territory almost entirely suitable for cultivation, the Mossi...cultivates what he needs’ (Binger L.G. 1895, p.501). How were agriculture and livestock rearing, its main production activities, practised in such a context?

The concept of production

The activity of production, agriculture in particular, which was the most widely practised, was in perfect continuity with all the manifestations of life, in close contact with the supernatural powers. Through both work and ritual, the Moaaga farmer was expected to participate in the cosmic process of maintaining and periodically restoring life. His efforts were meaningful only insofar as they coincided with the physical, social and religious development of the order willed by the gods and maintained by the ancestors or those who derived their authority from them. The tool or technique of production was not in itself effective. In order to obtain the material and consumer goods necessary for subsistence, it was the understanding between men and their agreement with the spiritual powers that were important compared to efforts to cultivate. Deliberately created disorders disrupted the natural order as well as the social order.They provoked sanctions in various forms: drought, sterility, disease, death, etc., which seriously compromised the balance of things and relations between people.These disorders also had a disastrous influence on the production of subsistence goods.Conversely, abundant harvests were the sign of a collective and community life that conformed to the models of conduct bequeathed by the ancestors.Given the importance of this activity, numerous rites and prohibitions had been instituted to control the behaviour of men or between men and supernatural powers, helping to promote agricultural production.

Joint production work was also preferred to individual work, and was considered to be more productive. When large numbers of workers came together, there was much to celebrate, and the drudgery of the work was lessened. These work meetings were also opportunities for intense social interaction. According to J. Boutillier (1964, p. 38), ‘ ... as if this way of proceeding compensated for the absence of employer-employee relations in this traditional system; to bring together and convene a cultivation company on a field is, from the point of view of production, an act analogous to the recruitment of farm labourers for a period of time; except that the formula accepted by custom is less flexible, that, from the point of view of economic calculation, it presents complex features (remuneration, productivity of this work carried out as a feast) and, finally, that it entails social obligations that come under the general network of rights and obligations’.

Multiple meanings were attached to working the land in addition to those relating to its production function.The organisation of economic production therefore provides a particularly significant insight into this society's philosophy of life.It clearly shows how the various institutions were organised to ensure the survival of this people in its traditional forms.It sheds light on the values mobilised to achieve this objective, and the strategies implemented according to circumstances.

The other significance of the practice of agricultural production lies in the context of community life. Each person's efforts were to benefit everyone, because the prosperity of the group was more important than individual success. :

The same rule governed economic relations at the level of wider social groupings such as lineages, neighbourhoods and groups allied by matrimonial exchanges. Various forms of community work were developed to organise mutual aid in the production of subsistence goods. Mutual aid demonstrated and strengthened the unity and cohesion of groups. It helped to ensure the integration of foreigners into the community that welcomed them. Very often, the reasons for cooperation were as much social as technical or economic.

But since European colonisation, the real historical pivot, the traditional conception of the Moaaga's existence has been turned upside down. Every man for himself has taken over from the common destiny. The individual has learned to live alone in the face of history and eternity. It is as if man has reluctantly rejected metaphysical hope, the comfort of a saving cosmology or the benefits of the supernatural.

Believing only in himself and knowing that he lives only once, this type of clarity is dear to him but it also puts him in a bind. The collision of this existential knowledge has engendered in the colonised Moaaga a kind of anguish that makes him a helpless individual faced with the choice of solutions to the problems he encounters, solutions that he no longer perceives as a purification, a liberation, or as a dissolution of his being.

The Moogo is now part of a multi-ethnic whole, forming a country where large concentrations have wiped out the Moaaga's original sense of communitarianism in the system of exploitation and distribution of goods. This man is perceived from within, as some precepts claim, as a ‘stone-less’ fruit, compulsively committed to paths that lead nowhere.

This new man, the fruit of the multicultural mix that has characterised the country since its constitution, is an educated person with a fertile imagination and a different concept of living together. Today's Moaga society belongs to a world whose borders are open to other ideas and concepts of progress and development. Moogo has also ceased to reflect the world or the universe, becoming a tiny speck in it. What are the challenges facing Moaaga?

Moaaga philosophy and the issues and challenges of the 21st century

Today, Moogo, which is located in a tropical climatic context characterised by a diversity of landscapes, has experienced remarkable influences in its diversity of groups, its cultural and dialectal variances and their corollaries in its philosophy of life. The Moogo landscapes have experienced difficult climatic and ecological situations, linked to unfavourable natural conditions and anthropic actions, some of which have been overcome thanks to the combined interventions of the various development players. Likewise, the Moose communities have also experienced socio-political and cultural turmoil, which they have been able to overcome thanks to their cultural resources, which promote a better way of living together. However, against a backdrop of continuing global warming marked by, among other things, reduced rainfall, shrinking isohyets and plant cover, ongoing soil degradation and their corollaries of increased risk of natural disasters, and also against a backdrop of globalisation and accelerated social change, marked by individualism, intolerance, the rise of violent extremism, the hegemony of the rich countries and the prevalence of poverty, the natural environments on the one hand and the traditional philosophy of life of the Moose communities on the other find themselves at the crossroads of numerous environmental, social, economic, spiritual and ethical issues.

Environmental issues

The adverse effects of climatic vicissitudes, the most palpable manifestations of which are the recurrent droughts that have affected the Sahel in general, have not spared Moogo, where the same phenomena of degradation of natural resources, decline in agricultural production and erosion of biodiversity have also been noted, with unfortunate consequences in terms of food insecurity and exacerbation of situations of destitution and even poverty, especially in rural areas. Numerous efforts have been made by the Government to design and implement several projects and programmes to curb these ills. It has to be said that these efforts have not always produced the expected results, due to the complexity of the challenges and the lack of human, technical and financial resources needed to address the country's many concerns. We find ourselves in a territory marked by several centuries of pressure and exploitation that have spared only a few gallery forests around rivers and ponds, sparse forests and savannah with woody cover over more than half the territory.

In these circumstances, more needs to be done to conserve biodiversity, adapt to climate change, combat pollution and so on. The close correlation between environmental degradation and the deterioration in the living conditions of the Moose populations, particularly through loss of opportunities, reduced income from the exploitation of natural resources, vulnerability to natural hazards, etc., is an important reason why communities and other stakeholders should make a reasoned choice to systematically take account of environmental protection in all public and private actions aimed at achieving equitable growth and improving basic environmental conditions.

In such a context, it is essential to step up action to conserve biodiversity, adapt to climate change, combat pollution and so on. The close relationship between environmental degradation and the deterioration in the living conditions of the Moose populations, particularly through loss of opportunities, reduced income from the exploitation of natural resources, vulnerability to natural hazards, etc., is an important reason why communities and other stakeholders should make a reasoned choice to incorporate environmental protection into all public and private actions aimed at achieving equitable growth and improving basic environmental conditions. It is therefore essential to take up the challenge of optimising the transmission of endogenous values, knowledge and know-how in the field of environmental protection through formal and non-formal frameworks.

Social issues

The diversity of groups, their practices, their cultures and their religion, which prevails among the Moose today, makes it abundantly clear that the system of values to which they are attached is a factor that contributes to stability and social peace. Some of their well-known cultural practices and expressions, such as the tradition of hospitality, kinship and the system of filiation, the institution of royal justice (wemba) and rakiire (joking alliances and kinship), promote better co-existence and help to regulate social tensions. This has been demonstrated in the mediation and resolution of socio-political crises, when the institutions of the Republic have shown their limitations, as during the socio-political events that have occurred in the country in recent years. The challenge here is to promote, maintain and even strengthen these traditional mechanisms of social regulation.The culture and foundations of traditional religion, together with its ethical values and deontology, as a matrix of reference points, meanings and identities, could be a vector of information and training for citizens, education and the sharing of knowledge and know-how, thus helping to build strong individual and collective personalities and the unity of peoples and countries. Promoting education in culture, traditional religion and its ethical principles is therefore a key social, spiritual and ethical issue.

Economic issues

The view that development is essentially economic, material and financial and that human capital is not a direct creator of added value is still widely shared and seriously handicaps the implementation of ambitious public policies. However, some countries that have been able to preserve and develop their human capital, their cultural heritage and their own spiritual and ethical life are now benefiting from the growth momentum generated by investment in people.

As a result, human resources and their heritage are increasingly seen as a lever for growth, capable of helping to resolve the problem of skills training and their involvement in defining projects and programmes for the socio-economic integration of young people and women, for sustainable and profitable development for all.

Cultural issues

The constant reference to exogenous cultural values poses a serious challenge to the transmission of endogenous cultural values. This often abrupt change in cultural reference points is characterised by the adoption of attitudes that are often contrary to local habits. This has led to a rise in anti-social behaviour, immorality among young people, a lack of knowledge and consumption of local artistic practices, and so on. The heritage issues at stake in the development of all the continents are decisive, because they concern the construction of the personality of Man wherever he may be, and of strong cultural identities that are essential to confer on every individual on this earth, self-confidence and self-esteem, two qualities that are today greatly eroded but so essential to human creativity. To achieve this, it is incumbent on governments to introduce the teaching of endogenous cultural values into their curricula, and Burkina Faso would benefit from exploiting the common values shared by the Moose. This act of transmission will also be underpinned by the official recognition of certain practices, such as communitarianism and harvest festivals, which, while uniting other communities, are a guarantee of solidarity.

Adaptations of the traditional Moaaga philosophy

From the above description, it can be said that the traditional Moaaga philosophy, which is specific to a given African culture, has several aspects from which it can be adapted to the context of globalisation and contribute to the construction of harmonious living together in a more humanised world.

Here are some general ideas, although it is important to note that any adaptation should be carried out with respect for the fundamental values of this people's philosophy and in consultation with the members of the Moaaga community.

Exogamy and the limitation of matrimonial prohibitions between the nakombse and other social categories. These two social rules were a powerful means of attracting and integrating many groups into society, including foreigners.

Hospitality: among the Moose, each chiefdom measured its importance and credibility in relation to the others by the attraction it held for neighbouring populations.The rulers knew that the influx of foreigners helped to increase their military and economic power, as well as their prestige. For this reason, foreigners wishing to settle in a given territory were always welcome, provided they did not contravene the rules and customs of the host environment. Adapting this principle of life and incorporating it into the universal could help to make every individual a citizen of the world with rights and duties, so that there are no more refugees and stateless people.

The principles of customary and religious life: through laws governed by habits and customs, codified around religion, the Moose had succeeded in instilling in their subjects a prudent fear of the ancestors and of tenga (earth goddess), a vengeful goddess whose omnipresence was resented, and in the rulers a moderation and wisdom that appealed to and reassured the people. Taking into account this principle of life with universal values could help to ease tensions in the world.

Principles of social justice: The Moose had established hierarchical orders in society, placed under the governance of great custodians embodying authority, guarantors of peace and social cohesion, and who acted as judges. These institutions are also likely to inspire universal principles of life. For example, against the imperfection and abuses of the justice of the rulers, there were other means of recourse, presenting the ancestors and divinities as impartial judges whose sentence was final, a complex system of filiation and alliances (joking kinship) and numerous totems and prohibitions enabling them to contain and reduce abuses.

There was also the royal pardon, one of their inventions for rescuing certain individuals in trouble with the law. An individual who applied could obtain a pardon and a reprieve from their leader. The request was made through a person known as Wemba. Wemba was originally the elder sister of Naaba Wubri, the founder of the kingdom of Ouagadougou, who was given a power similar to that of mediator in modern society. All the kingdoms had their Wemdamba (plural of Wemba), daughters or sisters of the rulers, women of authority with philosophical and political functions. They embodied forgiveness and hope, and the trust of their subjects in the justice of their chiefs. In the imagination of men, the Wemdambas had become women of love, whose invocation led to speculation and fantasies about their (supposedly) overflowing sexuality. Through fiction, this institution made people dream and gave them hope where, at times, things seemed impossible.

The principles of equal opportunity: through its selective and competitive nature, the Moaaga political power was able to keep ousted princes at bay, so that they became talse (common men), as well as ennobling common men who distinguished themselves through their work and merit in the service of power. This policy of social promotion facilitated the passage of many individuals from the category of slaves (yembse), to free men, then to dignitaries and advisers to the sovereigns, even the most important. This principle of equality and social promotion is also likely to instil the values of fairness and equality universally enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but whose application is undermined in the capitalist world of outrageous and savage competition. These principles could include concepts such as respect, tolerance, justice and solidarity, which are values shared across different cultures. They should also include openness to intercultural dialogue and the exchange of ideas between different cultures. Globalisation encourages communication between people from all over the world, and the Moaaga philosophy could serve as a basis for facilitating this intercultural dialogue by emphasising mutual understanding.

The universalisation of the Moaaga principles of life must also take into account their principles of sustainability and respect for the environment. We have seen that some elements of the Moaaga philosophy emphasise connection with nature and sustainability. Globalisation has implications for the environment, and traditional Moaaga wisdom offers useful insights for promoting a respectful relationship with nature on a global scale.

Furthermore, given that globalisation has led and continues to lead to cultural homogenisation, the moaaga principles of cultural life, on the other hand, promote cultural richness and diversity. Taking this principle into account underlines the importance of preserving and celebrating cultural differences, in line with the 2005 UNESCO Convention on the Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions.

The contribution of the traditional Moaaga philosophy of life to positive transformations in our world also covers aspects of ethics in business and politics. This includes notions of social responsibility, fairness and transparency in economic and political interactions on a global scale, inspired by the Moaaga concept of Wealth and Good. Principles in this area include those relating to education based on Moose values, which should be encouraged to inform education systems to promote values such as wisdom, benevolence and the pursuit of knowledge. They also encompass the Moaaga philosophy of reconciliation and peace, which offer perspectives on conflict resolution and peace-building. These principles can be applied worldwide to encourage the peaceful resolution of disputes between nations, especially in the Middle East.